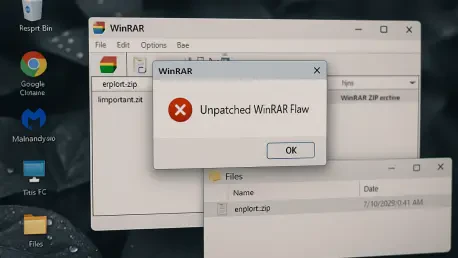

With us today is Rupert Marais, our in-house security specialist, whose expertise in endpoint security and cybersecurity strategies offers a critical perspective on today’s threats. We’re delving into a widespread vulnerability in a piece of software that many of us have used for decades: WinRAR. This single flaw has become a gateway for a startlingly diverse range of attackers, from state-sponsored espionage groups to financially motivated cybercriminals. Our conversation will explore why this “forgotten software” poses such a significant risk, particularly for small and midsized businesses, the clever technical tricks attackers use to maintain persistence, how they exploit professional trust, and what the slow patching progress reveals about our collective security posture.

Small and midsized businesses are considered highly vulnerable to this threat. Given that WinRAR often sits unmonitored on systems for years, what makes this “forgotten software” so ideal for attackers, and what simple audit steps can SMBs take to manage this risk?

That’s the core of the problem, isn’t it? The most dangerous aspect of this vulnerability is precisely that WinRAR often sits quietly on systems for years. It’s the digital equivalent of a dusty, unlocked back door. Users and even IT teams diligently patch their operating systems and browsers, but a vulnerable archive utility remains completely untouched and forgotten. From an attacker’s perspective, this is a perfect storm: the software is trusted, it’s unmonitored, and it only needs to be invoked once at the right moment to compromise a system. That combination makes dormant tools like WinRAR a persistent and often overlooked risk, especially in SMBs where software inventories might not be meticulously managed. For these businesses, the first step is a simple audit: run a scan to identify all installed instances of WinRAR. Then, implement a policy to either update it immediately to the patched version or, if it’s not essential for business operations, uninstall it completely.

We’re seeing both espionage groups and financially motivated criminals exploit this flaw. How do their attack campaigns typically differ, and could you detail the technical steps they use involving Alternate Data Streams to achieve persistence on a target’s machine?

The motives are different, and so are the methods, even if they leverage the same flaw. State-sponsored groups from places like Russia and China are playing a long game. They use this vulnerability for espionage, aiming for persistent, quiet access, often targeting sensitive entities like those in Ukraine. Their goal is information. On the other side, you have the financially motivated criminals. They’re looking for a quick payout, using the exploit to deploy commodity Remote Access Trojans (RATs) and information stealers against commercial targets to steal credentials or financial data.

The technical execution is quite clever. They craft a malicious archive file where the payload isn’t just sitting there. Instead, they conceal it using a Windows feature called Alternate Data Streams (ADS). So, when an unsuspecting user opens the archive, they see a harmless decoy file, like a PDF. But hidden within that file’s metadata, in the ADS, is the malicious payload. The exploit then uses a path traversal trick to write this hidden payload directly into a critical system folder, most commonly the Windows Startup folder. The user logs off, thinking they just opened a document, and the next time they log in, the malware executes automatically, giving the attacker a persistent foothold on their machine.

Attackers often target professionals in roles that require frequent file exchanges. How do threat actors manipulate this inherent job-related trust, and what specific training or security awareness anecdotes have you seen prove effective in preventing employees from opening malicious archives?

This is where the human element becomes the primary target. Attackers are incredibly savvy about targeting roles in technical, operational, or administrative functions where exchanging compressed files is just part of the daily grind. They understand that for these employees, trusting and opening shared files isn’t carelessness; it’s a job requirement. They’ll craft a spear-phishing email that looks like it’s coming from a known partner or an internal workflow, with an attachment named “Q4_Financial_Report.rar” or something equally plausible. The employee’s muscle memory is to download, extract, and open.

In terms of training, I’ve seen simulation exercises work wonders. We send out a benign but realistic-looking phishing email with a harmless archive. When an employee clicks it, instead of getting infected, they’re redirected to a short training module explaining the tell-tale signs they missed. It creates a powerful, tangible memory. Another effective anecdote is telling the story of a real incident, anonymized of course, where a single click on a zipped invoice led to a company-wide ransomware attack. Making the threat feel real and personal, rather than just a line in a security policy, is what truly changes behavior.

A patch for this vulnerability has been available for months, yet exploitation remains widespread. What does this gap between patch availability and real-world application tell us about organizational patching priorities, and what metrics should security teams track to close this window of opportunity for attackers?

This gap is a stark and frankly, concerning, indicator of a systemic issue in organizational security. It tells us that many businesses operate with a tiered sense of urgency. They’ll jump on a critical operating system or browser patch, but a utility like WinRAR, despite its high-severity CVSS score of 8.4, falls to the bottom of the list. It’s seen as less critical, yet as we’ve seen, it provides a direct, and now widely known, path into the network. The fact that threat actors began exploiting this as early as July 18, 2025, even before some public disclosures, shows how quickly they move. The months-long delay in patching on the defensive side is a massive, open window of opportunity for them.

To close this window, security teams need to move beyond just tracking “patch compliance.” They should be tracking “time to patch” for different severity levels and software categories. A key metric is measuring the time from when a patch is released to when it’s deployed across 95% of endpoints. They should also track the number of legacy or “forgotten” applications on their network. If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it. Reducing that “time to patch” metric for all software, not just the usual suspects, is the only way to effectively shrink the attack surface.

Do you have any advice for our readers?

Absolutely. Treat every piece of software on your network, whether it’s used daily or once a year, as a potential entry point for an attacker. The concept of “install and forget” is a dangerous relic of the past. My advice is to adopt a mindset of continuous software hygiene. This means regularly auditing all installed applications, not just the big ones. Keep everything fully up to date, and don’t be afraid to uninstall software that’s no longer needed. A smaller, well-maintained software footprint is a much harder target for attackers. Remember, security updates are not optional suggestions; they are critical defenses you need to deploy the moment they become available.